Heart Rate Variability

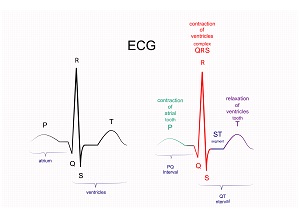

Heart Rate Variability or HRV is a measure that looks at the changes in the time between successive heart beats. Instead of being a measure of the number of heart beats in a given time (heart rate), HRV looks at the small changes in inter-beat-intervals (IBIs) in a given period of time. The inter-beat-intervals are also referred to as R-R intervals, reflecting the measurement of IBIs on an electrocardiogram (ECG) between the R (QRS) waveforms. HRV is typically measured in milliseconds (ms).

In measuring HRV, the frequency of heart rate signals is analyzed, as opposed to analyzing over time as with HR beats per minute. A mathematical process called “spectral analysis” is used to look at the HR power spectrum to determine the frequency of HR signals. Although heart rate over time (for example a one-minute HR) may be reasonably stable, the time between two heart beats can be considerably different.

This rhythmic fluctuation occurs between heart beats because of the changes in the sympathetic-parasympathetic balance that controls sinus rhythm in the heart. By looking at HR variability you can “noninvasively evaluate the relative contributions of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system at rest and during exercise. There are many physiological influences on HR variability frequency domains.” (Kenney 2019)

- When the sympathetic nervous system (stress/fight or flight) is more active, you will see a lower HRV. When the parasympathetic nervous system (rest, digest, repair) is more active, you will see a higher HRV.

- Influence is exerted in the sympathetic branch through the release of adrenaline which acts on nicotinic acetylcholine (ACh) receptors allowing the body to respond to challenges to survival.

- In the parasympathetic system, the vagus nerve and vagal tone respond to ACh to help conserve and restore energy by reducing heart rate, blood pressure, and the digestive system. (Singh 2019)

At this time, HR variability is primarily being used to examine physiological parameters in a few different ways:

- in chronic disease risk, cardiovascular disease risk, and health indications

- in looking at the impact of exercise training, especially in reference to functional and non-functional over-reaching, over training, and recovery.

HR variability is also considered an interesting marker for resilience and behavioral flexibility with applications for psychological and behavioral health. “It is well established that low HRV is associated with a broad range of medical and psychological health problems.” (Wheat 2010)

The goal is to maintain balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches. “If we have persistent instigators such as stress, poor sleep, unhealthy diet, dysfunctional relationships, isolation or solitude, and lack of exercise, this balance may be disrupted, and your fight-or-flight response can shift into overdrive.” HR variability can give insight into the ANS and be a valuable preventive tool metric.

A reduced HR variability (sympathetic) is associated with:

- worsened anxiety and depression

- increased risk of cardiovascular disease and death

- myocardial infarction

- chronic heart failure

- unstable angina

- diabetes mellitus

An increased HR variability (parasympathetic) is associated with:

- better cardiorespiratory fitness

- resilience to stress

- lower risk for many chronic diseases

A heart rate that is variable and responsive to demands is believed to bestow a survival advantage. The ability of the autonomic nervous system and sinoatrial node to respond dynamically to environmental changes results in increased HRV and generally indicates a healthy heart. A reduction in HRV is believed to indicate an inability or attenuation in the autonomic nervous system’s or sinoatrial node’s responsiveness to change.

HR variability moves to a healthier level with:

- more mindfulness

- meditation

- sleep

- physical activity (Faye 2010)

- regular aerobic exercise which increases vagal tone (Singh 2019)

Monitoring the autonomic nervous system (ANS) with HRV has become a useful tool for cardiovascular health and fitness:

- providing insight to cardiovascular risk evaluation and diagnosis.

- using HRV to alert athletes of overtraining and to optimize training. (Singh 2019)

A resting ECG for a healthy individual will show obvious high frequency values. HRV can lower with aging, sedentary lifestyle, mental load, and possibly overtraining. (Singh 2019) Cardiorespiratory exercise training increases vagal tone therefore increasing HRV.

HRV is the beat-to-beat alteration of the R-R interval of your heart rate. The gold standard for measuring HR variability is to analyze a strip of an electrocardiogram (ECG) to determine the IBIs. With this method being impractical and unavailable to the general public, HRV can also be tracked with a HR/heartbeat monitor (finger/wrist device or a chest strap) and the purchase of an app to analyze the data. There are other ambulatory methods for measuring HRV, many of which are not practical to use at this time but may become more practical as technology advances.

Common metric measurement devices use the following technology: (Singh 2019)

- ECG Devices: measurement of ECG still remains the most accurate way to measure HRV. Single lead ambulatory devices are available to analyze HRV.

- Photoplethysmography (PPG): “an optical technique that detects blood volume changes in the microvascular bed of tissue under the skin’s surface.” (Singh 2019) This method can be affected by motion and skin characteristics. It measures lower frequency components (sympathetic) and changes in blood volume with each heartbeat. Interest in PPG for measuring HRV is rising due to accuracy and wear ability, but there has been limited validation of this method for tracking HRV. Ongoing research is in progress to improve the accuracy of this method.

Wearables

- Most wrist worn tracking devices depend on PPG. Some now are adding ECG sensors.

- Chest straps with ECG electrodes that record ECG signals are more accurate. Some will send RR data to a cell phone via wireless technology. (Singh 2019)

- Wearable technology (PPG and ECG) for individual use, research use, and metric monitoring for health and disease risk continues to advance with HRV being a metric in the spotlight.

- Validity of wearables must continue to be studied for risk stratification, accuracy, and reproducibility. (Singh 2019)

When and How to Measure HRV (www.AgelessInvesting.com)

- HRV should be measured while you are sitting or standing upright. Parasympathetic saturation, a phenomenon caused while lying down, makes trends in HRV harder to interpret.

- HRV is best taken in the morning because your cortisol awakening response will make the reading different at any other time.

- Therefore, if you can’t take the reading within an hour of your usual time then don’t take it that day. Taking your reading at the wrong time will not accurately represent your awakened state and you may alter your baseline.

Emerging Science

Heart Rate Variability is a metric that is growing in interest and understanding. Using HRV as an indicator of heart disease and increased risk of sudden cardiac risk will provide non-invasive evidence that may be a catalyst for change in lifestyle habits for many at risk. HRV and the vagal response are also linking the predisposition and development of chronic disease directly to the importance of adequate sleep, stress reduction, mindfulness, and relaxation. This is a game changer, making the importance of “chilling out” and getting enough quality sleep something that goes from a luxury to a strong necessity that needs to be deeply entrenched in daily life. It is essential to health and quality of life. Our growing understanding of the role physical activity plays in HRV and vagal response will hopefully drive future generations to make physical activity a globally accepted way of daily life.

To Learn more about Heart Rate Variability and Heart Rate Training see the NAFC PowerCert: Heart Rate-Based Training for All Applications to earn .6 CECs.

References

- Kenney WL, Wilmore JH, Costill DL. (2019) Physiology of Sport and Exercise. 7th Human Kinetics.

- Wheat AL, Larkin KT. (2010) Biofeedback of Heart Rate Variability and Related Physiology: A Critical Review. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback (2010) 35:229–242.

- Singh N, Moneghetti KJ, Christle JW, Hadley D, Plews D, Froelicher (2019) Heart Rate Variability: An Old Metric With New Meaning In The Era Of Using MHealth Technologies For Health And Exercise Training Guidance. Part One: Physiology and Methods. US Cardiology Review VOL13: Issue 1: Spring 2019. https://www.aerjournal.com/articles/Heart-Rate-Variability-MHealth

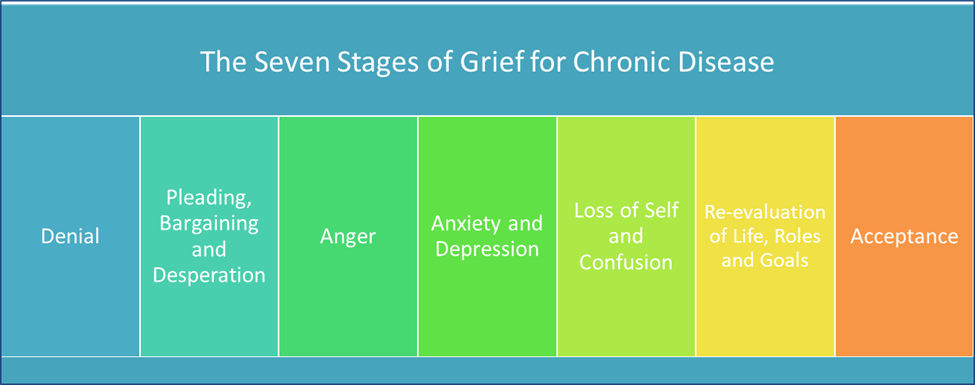

Exercise is an important part of treatment. Research shows that it may help slow the progression of disease. Be patient and creative when working with clients who have Alzheimer’s disease. Have an understanding of the disease progression, be vigilant in identifying physical decline, and overall, adjust their exercise program to maintain safety. The seven stage model that is commonly accepted and used to stage the progression of Alzheimer’s is provided below.

Exercise is an important part of treatment. Research shows that it may help slow the progression of disease. Be patient and creative when working with clients who have Alzheimer’s disease. Have an understanding of the disease progression, be vigilant in identifying physical decline, and overall, adjust their exercise program to maintain safety. The seven stage model that is commonly accepted and used to stage the progression of Alzheimer’s is provided below.